Old habits die hard: the lessons from COVID-19 have been taught before

Author: Connie Gamble | National Affairs Director

All things considered, it'd be pretty impressive to still be in the dark about the ongoing global pandemic. Having seen government measures evolve into increasingly strict demands, Australia is one among a constantly growing list of countries doing the same. As problems stemming from COVID-19 deepen the cracks of pre-existing inequalities and challenges, there is a lesson to learn here in light of our global response. Our short-termist tendencies and a prevailing 'to each their own' mentality amplify the global damage wrought by such events. This isn’t new information either. Our past experiences with pandemics and global threats have failed to adequately reshape our response efforts, and the world is currently feeling the devastating consequences. A departure from such dispositions is essential if we are to mitigate the harm of inevitable future events.

History never repeats

“[Influenza] didn’t end up being a pandemic that killed millions of people as we feared it would, but it should have been a wake-up call. By all serious estimates, COVID-19 is going to be a major killer”

Since the turn of the millennium, two pandemics have already had their unwanted time in the spotlight. In 2002, a different coronavirus strain was responsible for the SARS pandemic, which despite reaching many countries was contained within a matter of months. In 2009, the swine flu (H1N1 influenza strain) infected up to 1.4 billion people over the course of almost 20 months. Although differing in fatality, both pandemics presented serious challenges. We should have learnt from the past, however not all of us managed to do so.

Certainly, we could be forgiven for thinking that COVID-19 would have affected the world on a similar scale; only affecting certain cities without majorly disrupting the everyday workings of our economies. Yet, these expectations have already been surpassed in the worst way, placing healthcare systems under enormous pressure and necessitating incredibly high state expenditures in efforts to control the spread.

Health professionals have since explained our failure to fully learn from these past experiences. Steffanie Strathdee of the University of California San Diego's Department of Medicine saw the 2009 pandemic as what “should have been a wake-up call”, particularly given the fears at the time that it would kill millions. Our lack of preparedness following past outbreaks has left much of the world particularly vulnerable to the COVID-19 strain which is expected to be “a major killer” according to Strathdee.

One by one

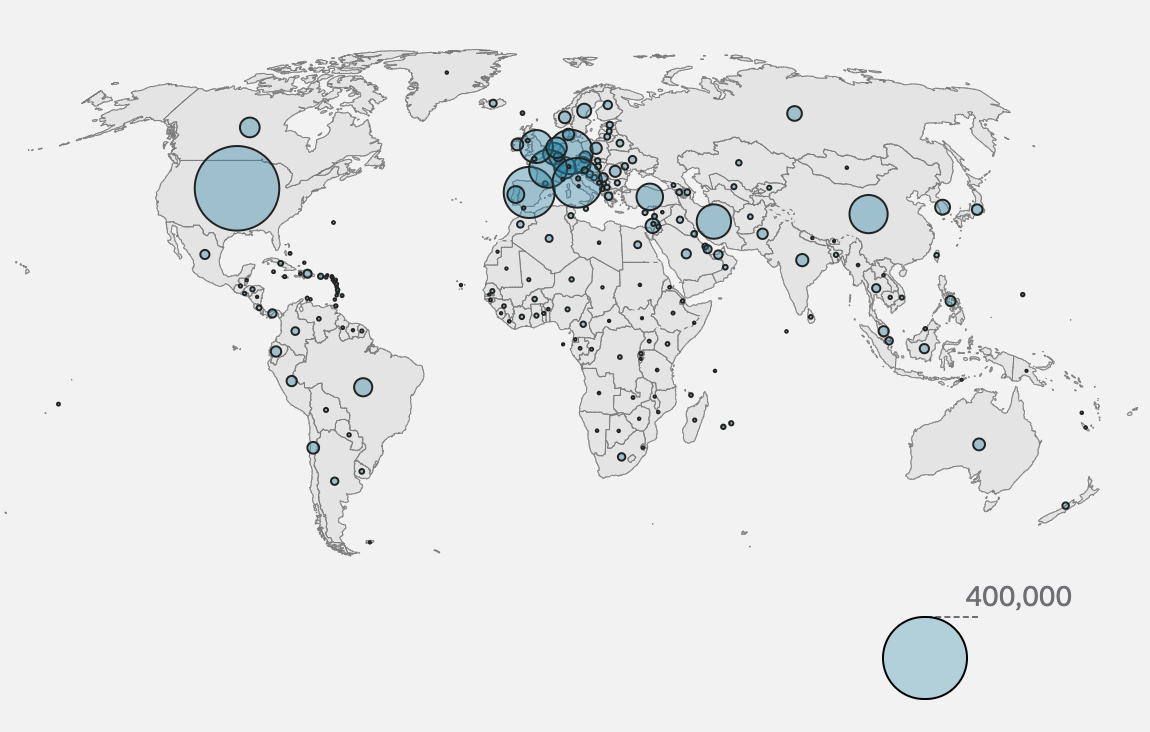

Our global response thus far has consisted of a country-by-country rollout of national policies. We were still attending university, travelling, working, and living as normal even as the virus spread beyond China. Inevitably it finally hit home, and subsequently we’ve felt a steady tightening of government measures. Almost naturally, the wave of incoming policies has mirrored the movement of the virus. This staggered policy rollout problem heightens the danger a pandemic can actually pose, as it lacks a united, broad containment strategy.

Global distribution of COVID-19 cases

Image source: BCC, data from Johns Hopkins University as at 9 April 2020

Despite global leadership from the World Health Organisation (WHO), national governments ultimately control the decision-making process, problematically leading to an inconsistency in approaches. The response time of not only individual nations, but of the global community, is incredibly important to curb the infection rate. Six months into the pandemic, that seems perfectly obvious. However, the coordination of a rapid, large-scale global response is easier said than done.

Intrinsic to human nature is a hesitation to act when we aren’t directly feeling the consequences. It’s been proven with an MRI machine, but the chances are that you’ve come to terms with the fact that we are rather selfish creatures. Sometimes we struggle to extend our empathy and reason beyond our immediate community, or even beyond today. You’re not always thinking of the hangover that’ll keep you bedridden tomorrow morning while you’re on a night out.

To an arguably great extent, we see these qualities in the behaviour of governments. While such behavioural differences are only natural to the global political community, a synchronised effort that learns from the past can only serve to save lives. It is worth noting that in such an intensely globalised world where intercontinental travel and trade are increasingly accessible, it is in the interests of every country, now more than ever, to curb global infection rates.

Don’t just think fast, act fast

If we take a look at two different responses, it becomes clear why we must trade our short-termist tendencies for proactive ones. South Korea and the United States both had their first confirmed case on the same day, and their current state of affairs is illustrative of the power of a proactive response to global pandemics.

On one hand, despite having the capacity to respond, the US lagged behind and only began seriously responding when the effects were felt on US soil. According to the chief executive of the Association of Public Health Laboratories, Scott Becker, American laboraticians “knew [they] could develop tests and were very capable of doing that, but we felt hamstrung,”. Even in Australia, the tense situation in the viral epicentre of New York City is receiving high news coverage.

In contrast, South Korea acted immediately by responding “like an army” according to Lee Sang-Won, a Korean CDC infectious disease expert. Having experienced a MERS outbreak in 2015 (a different coronavirus strain), officials acknowledged the possibility of a pandemic at once. Comparing the two, at the time of writing we are seeing a much more severe crisis in the US, while South Korea has been applauded for its success in controlling the virus. A key factor here is simply the relative intertemporal efficiencies of each state.

Perhaps you’ve noted that both South Korea and the US are both high income economies, and are wondering whether income dictates a government’s ability to respond. In certain ways it does, however timeliness is not necessarily hindered. If we consider the case of many West African countries, experiences with ebola have resulted in an aggressive and rapid mobilisation of resources to mitigate the spread of the virus. Schools were closed in Lagos, Nigeria despite having only eight confirmed cases. Comparatively, Australia saw a formal closure of schools when confirmed cases were well over 1000. So far, this fast and serious approach has kept numbers relatively low in many West African countries, despite often falling into the category of developing economies.

These differences in intertemporal efficiency speak to the importance of trading our short-termist instincts for proactive and adaptive responses.

How high can you bid?

“We’re not as wealthy. We don’t have as many ventilators, we don’t have as many doctors, our health system was in a precarious position before coronavirus”

The challenges this pandemic brings are capable of both perpetuating and magnifying pre-existing inequalities, regarding both public health and economic hardship. While a rapid policy response is largely dependent on government mobilisation, the physical element of bolstering and preparing healthcare systems involves obtaining the necessary resources.

This is one aspect where money comes in. The extreme desperation of countries scrambling to obtain adequate medical equipment has led to wealthier countries simply outbidding poorer ones. Regardless of national policy, certain countries in Latin America, Asia and Africa are therefore at risk of losing out in a ‘war behind the scenes’, as described by Dr Catharina Boehme, CEO of Foundation for Innovative New Diagnostics. Subsequently, lower income economies which may already struggle to fund healthcare systems must also face inflated prices for equipment. This is but one way in which asymmetric vulnerability can be seen in the global community.

Such barriers to sufficient preparation risks a “a massive reversal of gains made over the last two decades” in certain developing economies, according to UNDP Administrator Achim Steiner. This dangerously competitive scramble for resources during times of crisis threatens to worsen the inequalities we see today.

“The private sector is likely to respond to the highest bidder for many of these supplies, that’s just business”

With this in mind, it becomes clear that self-interested, divisive tactics will serve only to deepen pre-existing global inequalities and make everyone worse off. Their very global nature necessitates a global solution; collaboration in efforts against global threats is a step in the right direction to ensure global crises wreak no more havoc than necessary.

There will be a next time

COVID-19 has stopped us in our tracks with its unprecedented impacts; economies of all scales are desperately engaging resources as best as possible, decades of development are on the brink of being erased, and the vulnerability of developing states is being amplified. These consequences will stain for decades to come. Although we largely failed to learn from past pandemics, this is a critical time to recognise the importance of global collaboration and a departure from short-termism. We cannot predict the future, but we can prepare for it in a way that doesn’t fracture the global community and further disadvantage those already at risk. We can prepare for the next pandemic now. The price of not doing so makes change indispensable.

Food for thought

These lessons don’t apply solely to global health crises. We can see this pandemic as a canary in the goldmine, a warning bell that preparedness, intertemporal awareness and global collaboration are necessary adaptations. While pandemics by nature are unpredictable, anthropogenic climate change is a mere progression which we can predict and cannot stop. A response to such an indiscriminate force must be shaped by these same principles of collaboration and preparedness.